Diwali is the Prakrit way of saying Deepavali, a Sanskrit word meaning ‘the festival of lights’. This festival has been increasingly dominated by a single Hindi-belt narrative: that it commemorates Rama’s return to Ayodhya after his forest-exile. But Diwali is also about Krishna and Yama and Lakshmi and Bali. At the same time, it is a Jain festival marking the ascent of Mahavira to the heaven of Tirthankaras. And it is a Sikh celebration in memory of how Guru Hargobind enabled the release of 52 kings when he was finally set free from Jehangir’s prison. People have found many reasons to celebrate this festival, suggesting it predates all narratives.

Diwali has an organic root. It is a set of rites that takes place before and after the autumn new moon, marking the transition from monsoon to winter. This connection with nature makes Diwali a ‘pagan’ festival — an accusation once made by Muslim rulers and British colonisers for whom festivals were usually about the birth of prophets and martyrdom of saints. But as the Rig Veda says, ‘Even the gods came later.’

Diwali cannot be seen in isolation. It is the culmination of a long ritual cycle that begins as the monsoon recedes, with Ganesh Chaturthi (10-days of waxing moon when the elephant-headed god is worshipped with his mother Gauri draped in verdant green), extends through Pitru Paksha (the fortnight of waning moon when ancestors are venerated) and Navaratri-Dasara (the 10-days of waxing moon when the Goddess battles the buffalo-demon). The chain of worship leads naturally to Sharad Poornima, the full moon night when the Goddess sheds her anger and assumes her calm, benevolent avatar. She blesses those who spend the whole night waiting for her (Kojagiri Poornima of Maharashtra).

She dances as Radha with Krishna (Raas Poornima in Vrindavan, Mathura and Gujarat) and gives birth to the handsome Kartikeya (Kunvar Punei of Odisha). This is when Bengalis worship Lakshmi. After that comes a series of women-centred rituals like Karva Chauth (fourth night of waning moon) and Ahoi Ashtami (eighth night of waning moon), one performed for the well-being of the husband, the other for the well-being of children. Finally in Diwali, Sita returns home with Rama, Krishna releases Indra’s wealth from the clutches of Naraka, Bali-raja returns to Su-tala, located below the earth, and Lakshmi is churned out of the ocean of milk, before her brothers Bali, Yama as well as other denizens of invisible subterranean worlds bid her farewell.

Diwali marks the final phase of the four monsoon months known as Chatur-maas, during which Vishnu sleeps and monks do not travel. Who takes care of the world when the preserver sleeps? The task is left to yoga-nidra, or yoga-maya, described as Vishnu’s sister and Shiva’s consort. This is the time when the ground is wet and serpents rise from their underground homes, when buffaloes enjoy the muddy fields and when elephants revel in the rain. The cows, symbols of dry-land agriculture, step back, avoiding the slushy soil, preferring to cluster on dry bitumen roads, a common sight in Goa. Diwali clearly predates the Hindu epics. It belongs to an older, agrarian world, even before the Aryan migration, if one may provocatively say.

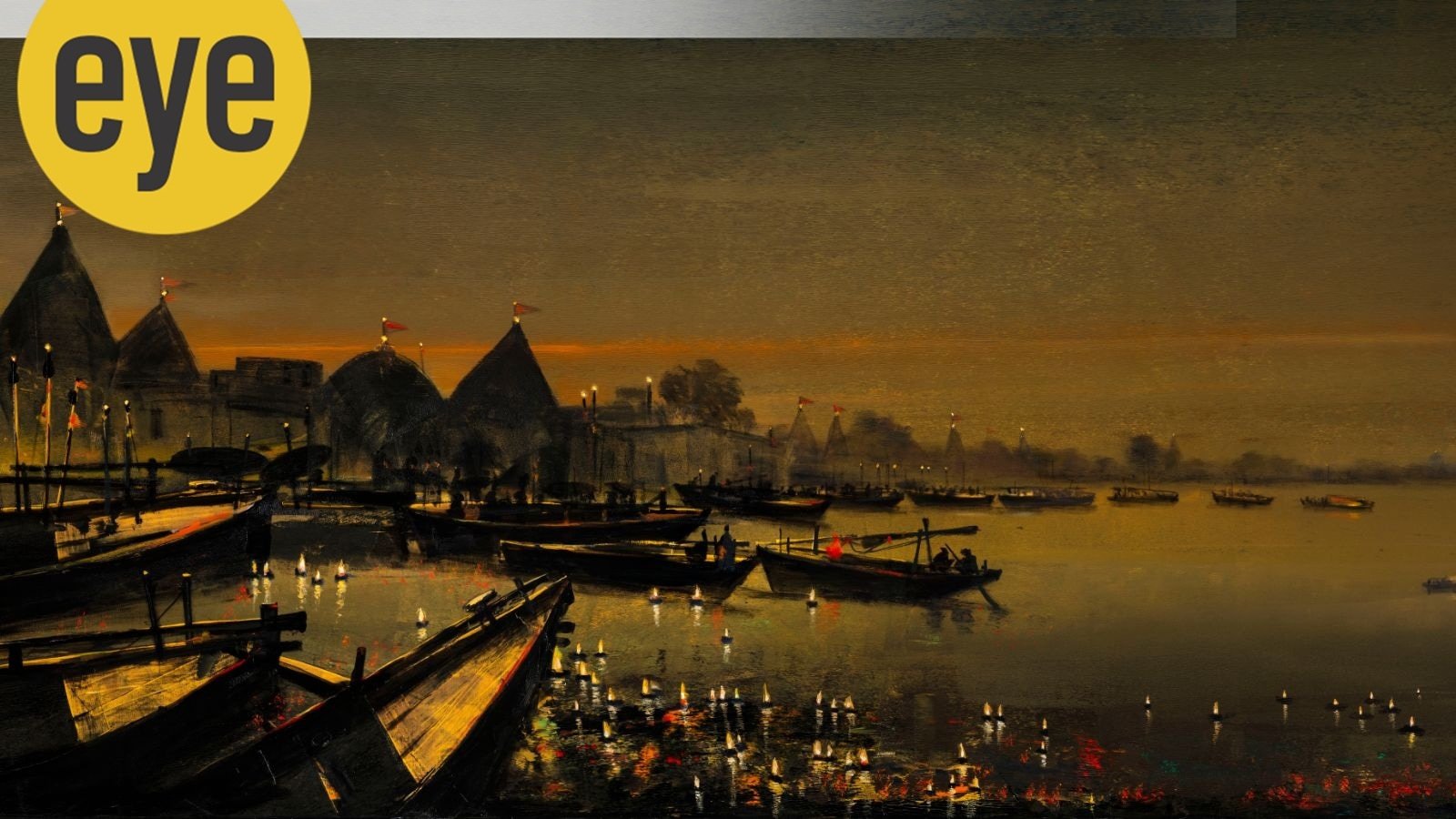

Village Kali Puja (1938) by Prahlad Karmakar (Photo by DAG)

Village Kali Puja (1938) by Prahlad Karmakar (Photo by DAG)

One cannot delink Dasara from Diwali. In Bengal, Dasara is about Durga, Sharad Poornima is about Lakshmi and Diwali is about Kali. For Rajput and Maratha kings, Dasara is about seema-ulanghan (boundary-breaking ritual). This was, since ancient times, the start of the military season, most suitable in India for warfare as soldiers generally avoided the hot summers and the wet rainy seasons. Diwali then is about the return of the warring parties. Dasara is when Rama goes south to battle Ravana. In the Deccan, Diwali is about Krishna going east — from Gujarat coast to Brahmaputra valley — to fight Naraka. Thus the two festival narratives crisscross India geographically.

Even within Diwali itself, regional variations reveal its true diversity. In the Deccan, Diwali is linked to the killing of Narakasura by Krishna and Satyabhama. It is a morning festival, celebrated with oil baths, lights and sweets — more about purification than conquest. In Goa, devotees burn effigies of Narakasura that are first paraded and then dismembered and disembowelled symbolically. There is no Ayodhya here; no Ravana.

Story continues below this ad

In Maharashtra, the days before Diwali are marked by Vasu Baras and Dhanteras, honouring animal and metal wealth. In Gujarat, Diwali night coincides with the beginning of a new financial year. Here, traders open new account books. Gambling is common during Diwali in Marwari households to find out who fortune favours. Houses are cleaned and crackers are burst to drive out the goddess of poverty and misfortune.

The day after Diwali is when Bali returns to his subterranean realm, leaving behind abundance, the mountain of food that is displayed in Krishna temples and known as Govardhan Puja. The second day of the waxing moon after Diwali is dedicated to brothers and sisters. Yama pays a visit to his sister Yami or Yamuna, who is Lakshmi. He is the god of accountants, worried if his sister (goddess of wealth) is in safe hands.

In Bengal, Diwali night is Kali Puja — when the fierce goddess, garlanded with skulls, is worshipped. The night before is Bhoot Chaturdashi, when families light 14 lamps to guide ancestral spirits home. This connection to the world of the dead is echoed in Assam and Odisha, where similar rituals of remembrance take place. Floating air-lamps or akash-deep are lit during Diwali to guide the dead back to the land of ancestors, Pitr-loka.

And what about food? Is it to be vegetarian Satvik as claimed by the Baniyas and Brahmins of the North? Is it a day of fasting? Yes, say some. No, say the Telugu Chettiars, the Marathas and the Rajputs. Many martial clans and tribal communities offer mutton to their family deity (kula devi). For them, the Diwali feast marks the arrival of fortune after labour and war. When someone refers to vegetarian offerings as ‘mainstream’ and meat offerings as ‘folk’, they reveal a casteist attitude where beliefs and practices of some communities are privileged over others. Such attempts to institutionalise Hinduism by homogenising can only be diluted by reclaiming Diwali’s regional diversity.

Story continues below this ad

Devdutt Pattanaik is a mythologist and author of over 60 books