The tragedy of a popular comic is that he — or she, as the case may be — is never allowed to break free from the burden of making people laugh.

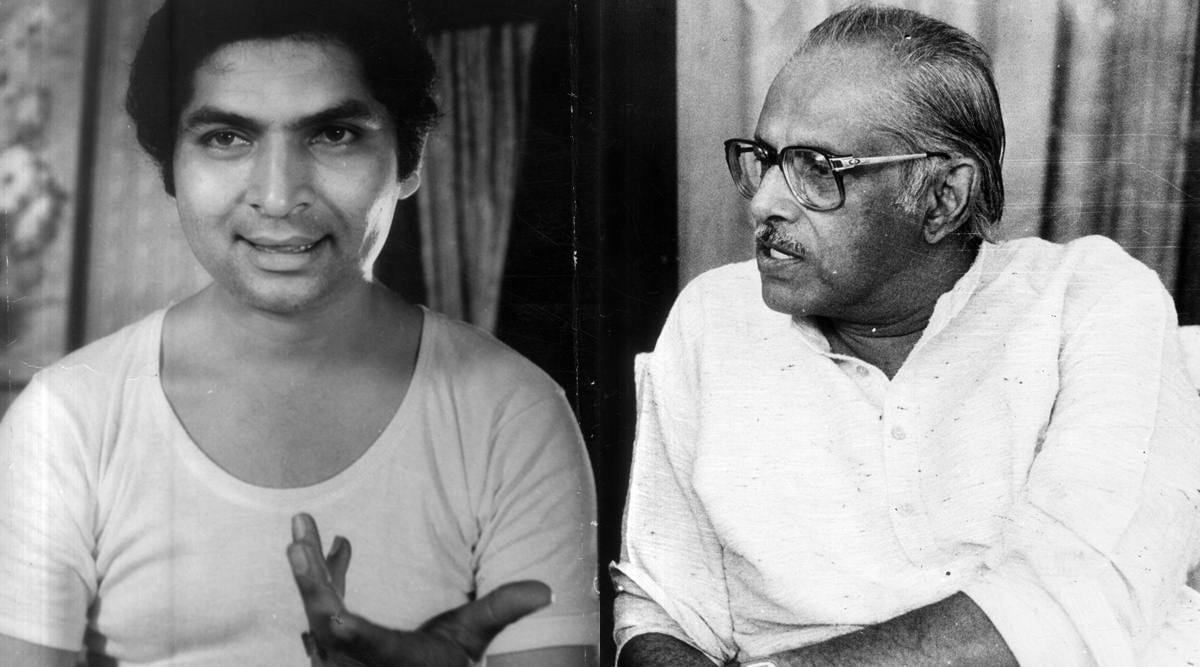

Govardhan Kumar Asrani was one of the Indian film industry’s finest actors whose best work was confined to strong supporting acts. Never peripheral, always integral, Asrani’s very presence lifted the films he did, and it was hard to find a film he wasn’t in during his most productive phase during the 1970s and ’80s.

He passed away yesterday after a prolonged illness, at the age of 84.

The FTII-trained actor had talent and timing, but he came into the Hindi film industry in an era when men who looked like him — unremarkable, not too tall, not too short, just your average Joe — did not get to play heroes. However good they may be, and Asrani was unfailingly good in everything he did on screen, they were relegated to playing the sidekick, which could either be the hero’s best friend, or the comedian who would come on for his track, and then step aside, letting the hero take over.

But if it happened to be Asrani, we would be cheering for the little guy on the sidelines as much as the big guy in the centre and front.

Sholay, currently celebrating its 50th year, is remembered not just for its leads — Dharmendra, Amitabh Bachchan, Hema Malini, Jaya Bhaduri, Sanjeev Kumar — but also for its villain, played gloriously by Amjad Khan, and the Angrezon-ke-zamaane-ke-jailor, played by Asrani in full ham-mode, furiously channeling his inner Chaplin-doing-Hitler: The stiff little moustache fronting a stiff little man strutting about, barking orders at his underlings — “aadhe idhar jao, aadhe udhar jao, aur baaki hamare saath aao”.

It’s the kind of line which becomes instantly iconic, and it has taken its place in the pantheon of great one-liners that Salim-Javed wrote for this desi spaghetti Western to beat all desi spaghetti Westerns, alongside those others like “kitne aadmi thay” and “tumhara naam kya hai, Basanti”. The jailor may have divvied his staff in two, but everyone was unified in their liking for the actor: The Angrezon-ke-zaamane-ka-jailor got cemented in peoples’ memories. But he was always more than just that in his long career of more than 300 films.

He did try his hand at being bad — in Gulzar’s Koshish (1972), he plays Jaya Bhaduri’s evil brother who is responsible for the death of her child, but it didn’t take. He tried to break away from the non-stop assembly line comic roles by becoming a hero in Chala Murari Hero Banne (1977), but the film didn’t do well, despite a clutch of sincere performances and starry cameos.

Through a production company he set up, he did manage to carve out leading roles in Gujarati movies, and that remained a flourishing parallel stream for him, even as his roles in Hindi cinema became sporadic after a point: The middle-of-the-road cinema where artistes like Asrani would automatically be a good fit was on its way out, ceding space to garish comedy.

He was one of those rare comedians who didn’t have to succumb to vulgarity (he could do borderline risque without appearing cheap, and that’s quite a feat) to grab our attention. He was fortunate that he didn’t have to go down the Shakti Kapoor-Kader Khan route, nor did he have to resort to the single-note schtick forced upon older comedians like Keshto Mukherjee. Asrani was versatile enough to play shades of the guy who could always be relied upon to do the right thing, something that was visible right from his early roles like Satyakam (1969), Mere Apne (1971), amongst many others.

His jodi with Rajesh Khanna — they did more than 20 films together, with Bawarchi (1972), Namak Haraam (1973), Aap Ki Kasam (1974), being some of the notable ones — was so popular that when Khanna appeared without him, viewers would feel as if they had been cheated. He worked with such directors as Hrishikesh Mukherjee and Gulzar who gave him roles where he could be life-like and regular; he also revelled in loud parts in the louder spectacles of David Dhawan, Rohit Shetty and Priyadarshan.

After a long gap, I caught sight of him in a web series (The Trial, Season 2) last month, playing a canny Parsi lawyer, jet black hair emphasising his ageing face, forced lines making me recall his glory days. One of my most favourite parts of his is one in which his function isn’t just to prop up the hero, but to act as able foil: In Hrishikesh Mukherjee’s 1973 Abhimaan, he played a secretary-cum-concerned friend to Amitabh Bachchan’s arrogant singer. And as always, Asrani made it better.

shubhra.gupta@expressindia.com