Retail food inflation has been in negative territory for the last four consecutive months ending September 2025. That’s against an average 8.5% annual rise in the consumer food price index during the eighteen months from July 2023 to December 2024.

The softening has to do with the easing of supply pressures – thanks to back-to-back good monsoons, after an El Niño-induced prolonged period of dry weather and above-normal temperatures in 2023-24 – and overall weak price sentiment in agricultural commodities.

Cereal glut

The supply turnaround is particularly evident in cereals.

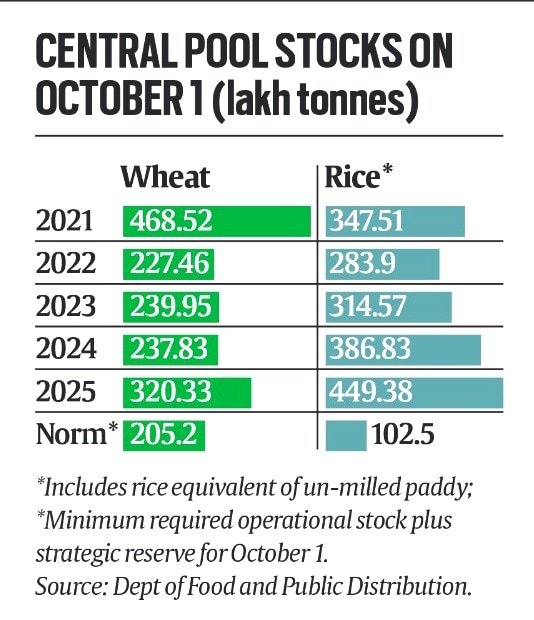

Table 1 shows wheat stocks in government godowns on October 1, at 320.3 lakh tonnes (lt), to be the highest in four years and over 1.5 times the required minimum buffer for this date.

Table 1.

Table 1.

The real glut, however, is in rice, where government agencies are not only holding an unprecedented level of stocks; these are also 4.4 times what is necessary to meet the needs of the public distribution system plus a strategic reserve for emergencies.

The oversupply is set to intensify as the harvesting and marketing of the new crop, which has started from October, picks up post Diwali. Indian farmers have planted a record 44.2 million hectares (mh) area under rice this kharif (monsoon) season, up from last year’s 43.6 mh.

The jump has been even more, from 8.4 mh to 9.5 mh, for maize. Not for nothing that the starchy feed grain is currently wholesaling in states such as Karnataka and Haryana at around Rs 2,000-2,100 per quintal, compared to Rs 2,200-Rs 2,300 a year ago and the government’s minimum support price (MSP) of Rs 2,400.

The case of soyabean

Soyabean is an illustrative example of a crop exhibiting bearish price sentiment despite not-so-good production.

Story continues below this ad

According to the Union Agriculture Ministry, the area sown under soyabean this year is 12 mh, down from 13 mh in 2024. The Indore-based Soybean Processors Association of India (SOPA) has estimated the output of the leguminous oilseed at a five-year low of 105.4 lt and below the 125.8 lt of 2024.

The 16.3% drop is being attributed to a decline in acreage as well as yields – from an average of 1,063 kg to 920 kg per hectare. That has, in turn, been blamed on excess rainfall, causing waterlogging and crop damage resulting in smaller size of grains and yield loss. The crop has also been impacted by yellow mosaic virus and aerial blight fungal disease attacks in many areas.

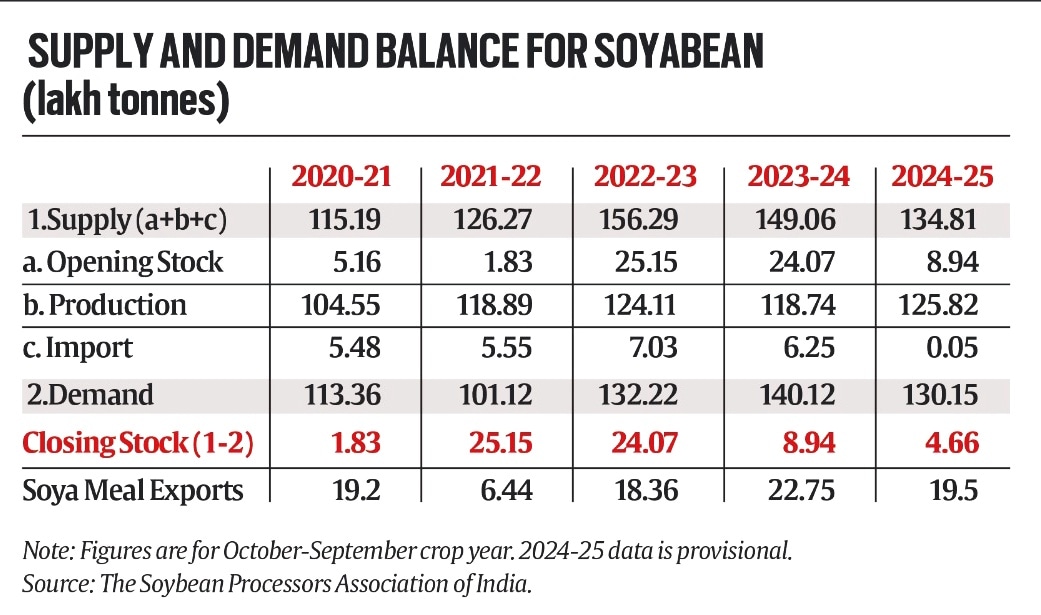

Table 2 shows the closing stocks of soyabean in 2024-25, at 4.7 lt, to be significantly below the 8.9 lt, 24.1 lt and 25.2 lt for the preceding three marketing years (October-September). The lower opening stocks, coupled with a subpar 2025 crop, should ordinarily contribute to a tight supply situation and bullish prices.

Table 2.

Table 2.

But far from bullish, soyabean is selling in Maharashtra’s Latur market at about Rs 4,100 per quintal, against Rs 4,300 last year at this time. The ruling wholesale price is, moreover, well below not just this year’s MSP of Rs 5,328 per quintal, but even the Rs 4,892 declared for the 2024 crop!

Story continues below this ad

Why are soyabean prices low? The answer is sentiment, which is weak globally on account of bumper harvests in the three major producing countries: Brazil, the United States and Argentina.

That is reflected in export prices of soyabean meal delivered at Indian ports falling from an average of $490 per tonne in September 2024 to $398 in September 2025. In quantity terms, too, exports dipped from 9.1 lt in April-September 2024 to 8.4 lt in April-September 2025.

One tonne of soyabean yields roughly 175 kg (17.5%) of oil and 820 kg (82%) of meal. The latter is basically the residual protein-rich cake after oil extraction. While soyabean oil is sold in the domestic market, the meal is both exported and consumed within the country, largely for use as a poultry and cattle feed ingredient.

In the 2024-25 marketing year, soyabean meal exports amounted to 19.5 lt, with domestic feed and food consumption estimated at 62 lt and 8 lt respectively.

Story continues below this ad

Soyabean processors are, at present, realising Rs 31.5 or so per from meal and Rs 118/kg from oil. That translates into a gross realisation of Rs 46,480 from processing one tonne of bean. Deducting Rs 2,000 of processing costs (towards hexane/chemical solvent, fuel, electricity, labour and fixed overheads) and another Rs 2,000 of transport-cum-market expenses (including mandi fees and labour charges, middleman commission and bagging), the maximum price payable to farmers would be Rs 42,450 per tonne.

That’s close to the Rs 4,100-4,200 rate prevailing in Latur or Madhya Pradesh’s Dewas mandi today. “We (processors) don’t decide the price that farmers get. The soyabean price is decided by our realisations from oil and meal. We simply pay that price,” says D.N. Pathak, executive director of SOPA.

Sluggish exports apart, soyabean meal prices are also under pressure from the increased supplies of so-called DDGS (distiller’s dried grains with solubles). This fermented mash – a byproduct of ethanol manufactured by maize and rice grain-based distilleries – contains protein, making it an alternative livestock feed ingredient.

Distilleries are selling DDGS from maize and rice at Rs 15-17 per kg. Given the Rs 31.5/kg price for soyabean meal, it isn’t surprising that the domestic consumption of the latter for feed has come down from 67 lt in 2022-23 and 66 lt in 2023-24 to 62 lt in 2024-25.

The post-Diwali challenge

Story continues below this ad

Through the second half of 2023 and the whole of 2024, the Narendra Modi-led government struggled to contain food inflation that was eating into the purchasing power of households.

With that battle decisively won, the shoe is on the other foot. It’s farmers, not consumers, that are at the receiving end now.

Almost all crops – whether maize, soyabean and cotton or bajra (pearl millet), arhar (pigeon pea) and moong (green gram) – are selling way below their MSPs. The sentiment is overwhelmingly bearish, even as the benefits of recharged groundwater aquifers and filled reservoirs from the surplus monsoon rains are likely to extend to the ensuing rabi (winter-spring) cropping season as well.

The coming weeks and months could see a shift in the government’s policy focus, from an excessively pro-consumer approach to one that is more pro-farmer. These may take the form of restoring import duties on cotton and yellow/white peas, besides stepping up MSP procurement of pulses and oilseeds under its price support scheme.